Kinky nanotubes

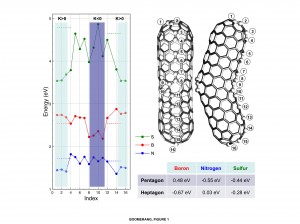

(Click image to enlarge.) Density functional theory calculations compare the energy necessary to substitute boron (red), nitrogen (blue) or sulfur (green) atoms for carbon atoms at 16 positions on a curved carbon nanotube (right). Where the curve is negative (K < 0), the carbon rings have seven atoms (heptagons) and it takes less energy for boron to substitute for carbon; boron selectively creates negative curves in the nanotubes and keeps the ends from closing, so they grow longer. Substitutional energy levels for nitrogen are lowest in pentagonal carbon atom arrangements, making nitrogen most likely to substitute for carbon at the positive (K > 0) positions. Researchers have found nitrogen gives rise to periodic raised rings along nanotubes, leading to bamboo-pole-like architectures. Sulfur can be accommodated in both pentagonal and heptagonal carbon rings and so promotes branched nanotubes.

In 2007, Bobby Sumpter and his Oak Ridge National Laboratory nanomaterials theory collaborators used computers to predict that adding a pinch of boron would produce kinks in carbon nanotubes. As an undergraduate student at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) the next year, Daniel Hashim guessed the curves might make these boron-doped nanotubes good energy-storing materials.

But no one expected what Hashim got when he actually used boron to contaminate the carbon in nanotubes – cylinders thousands of times thinner than a human hair.

“I didn’t know it was going to come out as a porous, three-dimensional solid framework” – a nanosponge big enough to hold in your hand, says Hashim, now a doctoral student at Rice University. “That was the big surprise. We didn’t have the insight at the time to understand that that’s what would happen.” Now researchers are touting these macro manifestations of nanotechnology as possible tools to clean oil spills, store energy, construct bones and meet other needs.

The Oak Ridge researchers used high-performance computing to help understand what’s happening at the atomic scale as these extraordinarily versatile black blocks grow. But it took an off-handed remark to link their work to the sponge-testing experimentalists. (See sidebar, “A spontaneous collaboration.”)

The scientists detail the material’s properties in a paper published online in Nature Scientific Reports:

• It repels water but sops up carbon-containing liquids, holding up to 100 times its weight in oil.

• The material is 99 percent air, so it’s remarkably light and absorbent.

• To get the oil out, just squeeze (tests show the sponges are still elastic after 10,000 compressions) or set on fire. The oil burns off, doing little harm to the reusable material.

• Because the material is made with an iron-based catalyst, magnetic fields can manipulate the sponges, making them easier to move or collect if they’re used for oil spill remediation or other purposes.

Boron, a common element that neighbors carbon on the periodic table and is found in laundry detergent, fiberglass insulation and other products, makes these high-tech sponges special. First, it “acts as a surfactant, which means it sits at the edge of the growth of carbon nanotubes and keeps them open,” says Sumpter, Chemical and Materials Sciences Group leader and director of Oak Ridge’s Nanomaterials Theory Institute. That helps the sponges grow to millimeters in length – extraordinarily large for such structures, says paper co-author Mauricio Terrones, a professor of physics, materials science and engineering at Pennsylvania State University and Japan’s Shinshu University.